My antepartum rounds reflect the impact of the pandemic - women struggling with substance abuse and mental illness fill the beds.

One patient, wearing her designated green hospital gown that signals “at-risk” status and assigned a one-on-one sitter, explained, (I paraphrase), “Isn’t it appropriate to have bad thoughts now? I have three kids at home – two I try to make the computer work for so they can attend school, a 1-year-old, and here I am pregnant again. We lost our jobs, tensions are high, we cannot visit or see anyone, we have no help…. At times it all just boils up and I explode. Then I think life is not worth living. I get over it, but yes, I have bad thoughts.”

As demonstrated by my patients, the very measures used to prevent the spread of COVID-19 increase the risk of depression and suicidal thoughts: economic stress, social isolation, decreased access to community, barriers to mental health treatment, and illness.1

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the national rates of anxiety increased nearly four-fold from one year ago. In 1999, national rates of anxiety in adults were 8.2%, whereas data from August 19-31, 2020, are 31.4%.

Similarly, rates for anxiety or depression have increased from 11.0% to 36.4%. All are higher in women, those with less education, and Black, Hispanic, and multiple other races.2

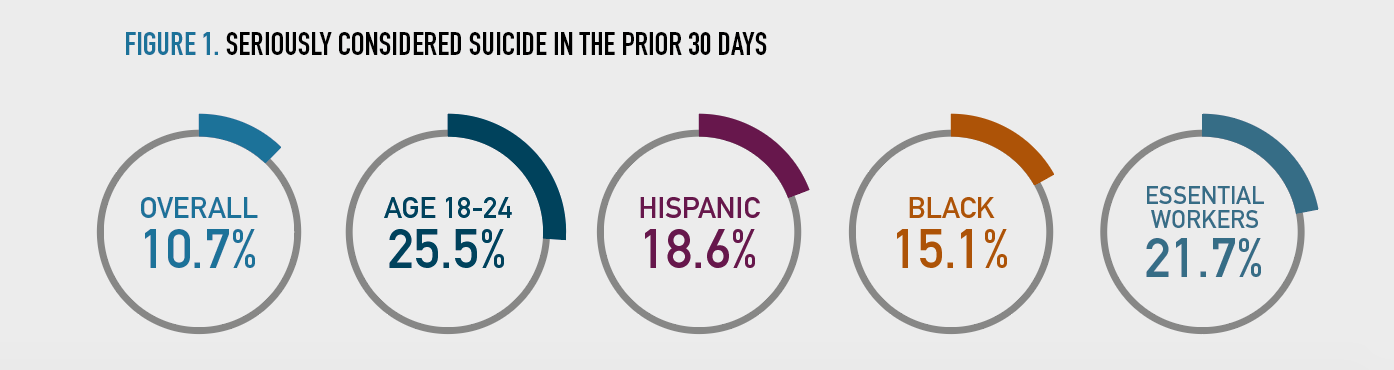

A separate survey in June found similar rates of anxiety or depression (30.9%). In addition, 10.7% of the respondents reported “having seriously considered suicide in the prior 30 days” – these were significantly higher among those aged 18-24 (25.5%), minority racial and ethnic groups (Hispanic 18.6%; Black 15.1%) and essential workers (21.7%)(Figure 1).3

Beyond its impact on our patients, it is vital to realize its effect on us as caregivers.

Figure 1. Seriously considered suicide in the prior 30 days

As the impact of the pandemic continues, our ob/gyn practices and families are affected. Eighty-three percent of obstetrics and gynecology residents are female – the highest percentage of any specialty4 – and they are often playing a dual role as the family’s primary caregiver in addition to practicing medicine.

Setting aside the burden of virtual schooling for both caregivers and children, the effects of social isolation and decreased accessto community are also affecting our children. They also mirror increased rates of anxiety and depression, yet may not have the access or resources for identification and treatment.

So what to do, what to do? In our practices, departments, and families, providing an opportunity for open communication and a safe space to share feelings without judgment is essential.Proactively, one of my colleagues’ practices meets biweekly with a psychologist. All of the providers gather and discuss both practice and personal stressors. Although predating the pandemic, this has been especially beneficial with an ongoing opportunity for open communication to discuss and identify solutions. These sessions help to identify feelings, conflicts, and provide strategies to communicate them effectively. They also allow a platform to discuss complications and poor patient outcomes, serving as a forum to process these deeply traumatizing events and rise, rather than stagnate, or worse, fall. We as physicians need this type of forum in order to heal ourselves.

Our patients and families deserve similar support and we should strive to help them get it. We need to provide opportunities for open communication in a safe space. Referrals to our colleagues in psychiatry and psychology are essential to ensure appropriate care. Although there is always a shortage of therapists, these at-risk populations need to be prioritized. Furthermore, we need to be on the alert for signs and symptoms of anxiety and depression in not only ourselves but also in our colleagues, families, and patients

__

Setting aside the burden of virtual schooling for both caregivers and children, the effects of social isolation and decreased accessto community are also affecting our children. They also mirror increased rates of anxiety and depression, yet may not have the access or resources for identification and treatment.

So what to do, what to do? In our practices, departments, and families, providing an opportunity for open communication and a safe space to share feelings without judgment is essential.Proactively, one of my colleagues’ practices meets biweekly with a psychologist. All of the providers gather and discuss both practice and personal stressors. Although predating the pandemic, this has been especially beneficial with an ongoing opportunity for open communication to discuss and identify solutions. These sessions help to identify feelings, conflicts, and provide strategies to communicate them effectively. They also allow a platform to discuss complications and poor patient outcomes, serving as a forum to process these deeply traumatizing events and rise, rather than stagnate, or worse, fall. We as physicians need this type of forum in order to heal ourselves.

Our patients and families deserve similar support and we should strive to help them get it. We need to provide opportunities for open communication in a safe space. Referrals to our colleagues in psychiatry and psychology are essential to ensure appropriate care. Although there is always a shortage of therapists, these at-risk populations need to be prioritized. Furthermore, we need to be on the alert for signs and symptoms of anxiety and depression in not only ourselves but also in our colleagues, families, and patients

__

DR. SPONG, editor-in-chief, is Professor and Vice Chair in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Chief of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. She holds the Gillette Professorship of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

__

__

References

1. Regar MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide Mortality and Coronavirus Disease 2019—A Perfect Storm? JAMA Psychiatry. Published online April 10, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed Sept. 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm

3. Czeisler ME, Rashon I, Petrosky E, et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020 CDC MMWR Aug 14, 2020 vol 69, No. 32

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Percentage of Women Residents by Specialty 2018. Accessed Sept. 21, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/sites/default/files/aa-data-reports-state-of-women-residents-specialty-2018_0.jpg

Medical Practice Supplies

VIEW ALL

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Yellow)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Yellow) Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Pink)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Pink) Manual Prescription Pads (Bright Orange)

Manual Prescription Pads (Bright Orange) Manual Prescription Pads (Light Pink)

Manual Prescription Pads (Light Pink) Manual Prescription Pads (Light Yellow)

Manual Prescription Pads (Light Yellow) Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Blue)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Blue)__________________________________________________

Appointment Reminder Cards

$44.05

15% Off

$56.30

15% Off

$44.05

15% Off

$44.05

15% Off

$56.30

15% Off

VIEW ALL PRODUCTS

.

No comments:

Post a Comment