EMRs were not so commonplace before the turn of the millennium. Less than 1 in 5 office-based doctors had an EMR before 2000 as compared to the estimated 88% in 2021 (Source: HealthIT.gov). I don’t know the 12% still doing paper charting, but let’s leave them be for now. We know that in 2010 the Federal government ‘incented’ practices to adopt EMRs as well as introducing payment delays for those still charting on paper. What I am interested in is the impact of EMRs on E&M coding. I checked in 2008, when about 42% of office-based physicians were using EMRs, and was interested in a follow-up.

In this article, I am focusing only on the E&M office follow-up codes – 99211-99215 – and looking at global trends. In future articles, I may delve into specialty specific trends or new patient/consult codes (younger doctors, Medicare used to have separate new patient and new consult codes).

Here's how office follow-up visits were coded in 2000:

99211: 5.5%

99212: 14.5%

99213: 53.7%

99214: 20.7%

99215: 3.2%

And in 2008:

99211: 4.3% (less 1.2% in raw delta)

99212: 9.7% (less 4.8% in raw delta)

99213: 48.9% (less 4.8% in raw delta)

99214: 33.1% (plus 12.4% in raw delta)

99215: 4.1% (plus 0.9% in raw delta)

And in pre-pandemic 2019:

99211: 1.2% (less 3.1% from ‘00 and 4.3% from ‘08 in raw delta)

99212: 4.8% (less 4.9% from ‘00 and 9.7% from ’08 in raw delta)

99213: 41.4% (less 7.5% from ’00 and 12.3% from ’08 in raw delta)

99214: 47.9% (plus 16.8% from ’00 and 27.2% from ’08 in raw delta)

99215: 4.7% (plus 0.6% from ’00 and 1.5% from ’08 in raw delta)

What we’ve seen is a continuing trend to using higher codes.It’s no surprise. EMRs are hard-wired to ensure clinicians document not only what is salient to the patient but also document things that have no bearing on the patient’s treatment. Many EMRs have built-in coding guide algorithms that are driven by the care documented rather than the care given.

Doctors have not gamed the system; instead, they have followed the lead of the Federal government in moving towards a coding system driven more by documentation than care. Add the obtuseness of E&M coding guidelines in the past 20+ years – a landmark study by Mitch King in the Archives of Internal Medicine demonstrated that both certified professional codes and physicians rarely find common ground on the ‘correct’ code for a documented clinic visit – and it is no wonder this trend of higher coding continues.

I applied a weighted average scale to the 2000, 2008, and 2019 E&M follow-up code usage to better demonstrate the change. Here’s the weighted average code for each year:

2000: 99212.99

2008: 99213.23 (+8.0% difference)

2019: 99213.50 (+17.1% vs. ’00 and +8.4% vs. ’08 difference)

All that means is that clinicians are using higher codes.

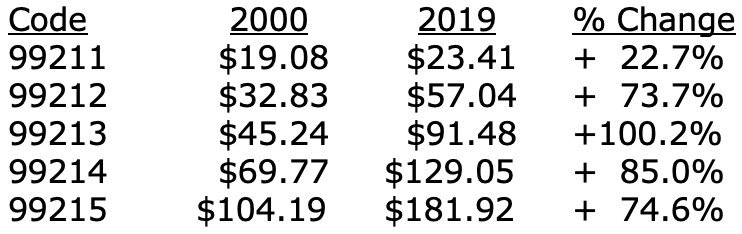

I used my home state of Virginia’s average Medicare reimbursement for 2000 and 2019 for my comparison, as there was no national average in the 2000 CMS database. Here’s what I found in terms of payment changes:

The shift to higher E&M coding is an unintended consequence of the Federal government’s plan to improve care through EMR adoption. It’s resulted in a higher total Medicare spend. When the aggregate spending target is missed, Medicare cuts are proposed like the 8.5% physician payment cut currently on the table for 2023. There are no easy answers.

My goal in this article was not to solve the Medicare funding problem. Rather, I wanted to test my hypothesis that EMRs have driven a trend to the use of higher E&M codes. I believe I have proven such. What I have not assessed is the source of these shifts, be it specialists, primary care, or a combination. It’s a great question for a geek like me and one I shall explore in a subsequent article.

15% Off Medical Practice Supplies

VIEW ALL

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Yellow)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Yellow) Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Pink)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Pink) Manual Prescription Pads (Bright Orange)

Manual Prescription Pads (Bright Orange) Manual Prescription Pads (Light Pink)

Manual Prescription Pads (Light Pink) Manual Prescription Pads (Light Yellow)

Manual Prescription Pads (Light Yellow) Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Blue)

Manual Prescription Pad (Large - Blue)

No comments:

Post a Comment